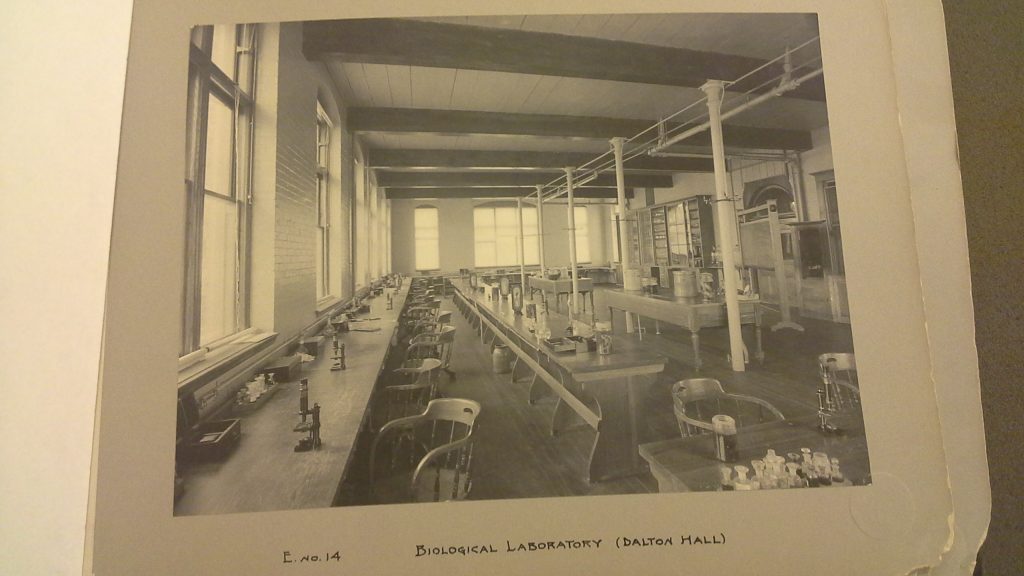

On the morning of January 3rd, I made the short train ride from Downingtown to Bryn Mawr to begin my “Winternship” with Bryn Mawr’s Digital Scholarship department. Starting last semester, I, along with three other Digital Scholarship Research Assistants, began working on the History of Women in Science project, headed by postdoctoral fellow Jessica Linker. For the first phase of the project, we will be building an interactive 3D model reconstructing a science lab in Dalton Hall, which, prior to 1938, housed the Biology, Chemistry, Physics, and Geology departments. This Winternship was a sort of extension of our work during the semester.

My co-Wintern Jocelyn and I spent the first week or so improving upon our digital skills by learning about several tools that may come in handy as we move forward with this project. After using MAMP to set up local servers on our computers, we got some experience using MediaWiki, the open-source software that powers Wikipedia and many other popular websites. I also completed a tutorial on Markdown, a programming language that allows the user to quickly and easily format text. The formatted text can then be converted to other file types, such as HTML. I then had the opportunity to try out the command line interface. When using the command line interface, rather than visually clicking and dragging on files and folders, you move, rename, copy, and delete files by typing commands directly into a plain black window. While this is a somewhat old-school way of doing things and can take some getting used to, the command line interface is a powerful tool that is, I’m told, useful for tasks that require a high level of precision. For this reason, it’s often favored by people who are doing, say, historical research—like us.

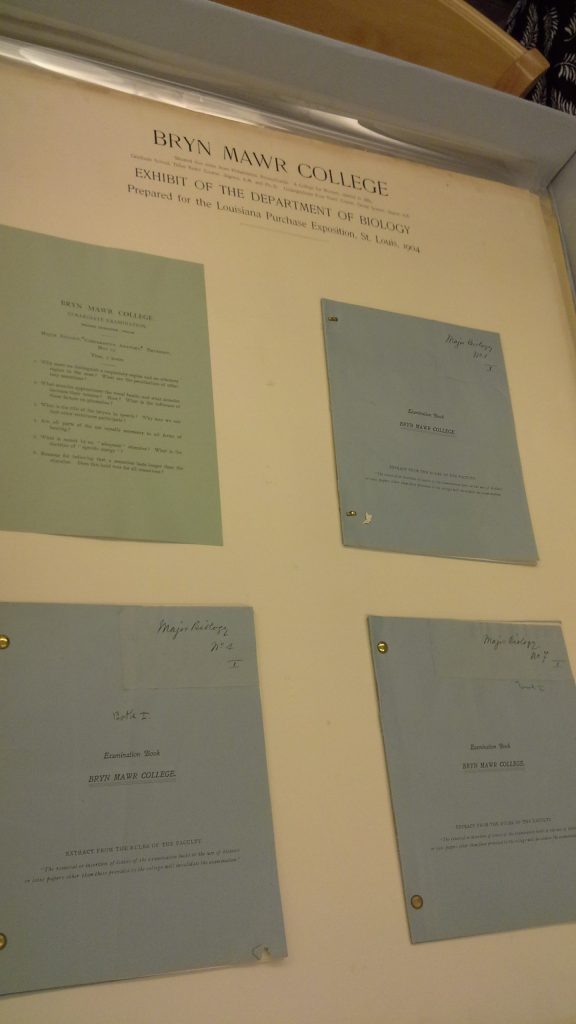

That brings me to the second component of our Winternship. One of our tasks was to begin collecting the historical information that we will need in order to build the 3D model of Dalton Hall. Before we were ready to jump into the archives, however, we got some practice transcribing selected portions of the diaries of Mary Whitall Worthington, which are available on Triptych. Worthington attended Bryn Mawr from 1906 to 1910 and went on to medical school at Johns Hopkins; sadly, she died before completing her studies there. You could hardly ask for a better introduction to historical research: Worthington’s diaries are engaging and funny, filled with descriptions of college festivities and the antics of her friends and classmates. Though many of her entries are concerned with pro-suffrage activism and social engagements, at times her interest in science and medicine shines through in both expected and unexpected ways. In one memorable entry, Worthington writes of being distracted from her biology homework by a pretty tree outside her window. She recounts, “It took me about ½ a second for the stimulus to travel along my sensory nerves to my central nervous system and so to my motor nerves causing me to spring from the window seat, seize a pen and begin to write.”

I’ve had a lot of fun these past few weeks broadening my digital competencies and gaining experience with historical and archival research. I’m excited to see the new directions we’ll take and the new voices we’ll encounter when the other DSRAs, Mimi and Linda, rejoin us at the start of the Spring semester.