Peyton Moriarty (’21), Digital Scholarship Summer Fellow

This summer’s DSSF project, ‘24 ‘31 Students Study Race, rolls together education, funding, collaboration, and the highlighting of important events in Bryn Mawr’s past which are intensely relevant to the institution today. In pursuit of that past, our group conducted extensive research. Due to the pandemic situation, our research this year was confined to online sources, but we were able to truly appreciate the variety of information–useful and not–that the Internet provides for the modern student. Researching online is not unlike recreational reading on Wikipedia: it is precariously easy to fall into an Internet hole of interesting but irrelevant information.As the project’s research manager, my role was to guide the group’s investigations: to identify which holes were worth falling down, during the 10 weeks of our work on the project. With that time limit in mind, which details were important to verify, to incorporate? Which were irrelevant, or took away from the exhibit’s meaning?

You can assume that all material which appears in the digital exhibit was determined to be contributive. Other information was less relevant. As an example, for my research on the embedded maps visible in the 1924 and 1931 exhibits, I acquired a foundational understanding of which transportation methods were available at the time. That endeavor produced particulars on the pre-highway American road system, and on some railroad stations which no longer exist. Determining whether this data was relevant was a complicated consideration, because that aspect of the project–the state of the transportation system a full century ago–was likely to be a lengthy endeavor in order to fully verify its information. It was therefore also likely to draw the exhibit’s subject away from its true purpose: highlighting the experiences of the people who attended the convention, particularly Black students traveling under segregation. I worked to include only the attendee-relevant information, and to periodically bring the focus back to the 1924 convention and the people involved.

Another example of tangential but still relevant information: at one point during our research, we sought out a contemporary audio recording of the spiritual “I Got Shoes,” which was performed at the 1924 convention. Among other potential sources, I discovered that the musical film George White’s 1935 Scandals (1935) contains a rendition of the song and it might be possible to copy the song from the film’s track. However, we ultimately didn’t need to use this method–while listening to the song “Little David, play on yo’ harp” in order to transcribe it, I realized that the song only occupied half the length of the recording, and that the other half was in fact “I Got Shoes”! The Library of Congress had included both of them in responding to our request for the other song.

There was a significant amount of other data that our cohort encountered, which we would share with each other during our tri-weekly group meetings. In this way, we could update each other on what we were seeing, and broaden everyone’s awareness about the history we were researching. So I thought I would share here some of the incidental material I collected:

Disclaimer: By their nature, these stories are under-researched, so some details may be incorrect.

In order of most to least relevant:

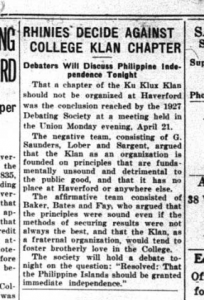

- In the same issue of Haverford News as an article about the 1924 conference, there is an article titled “Rhinie Debaters Will Argue Ku Klux Klan Question.” The article announces that a first-year debating group was set to argue the topic: “Resolved, that a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan be established at Haverford College.” In an article two weeks later, it was reported that the “negative team” had won out, arguing that “the Klan as an organization is founded on principles that are fundamentally unsound and detrimental to the public good, and that it has no place at Haverford or anywhere else.” The affirmative team, which lost, had argued that “the principles were sound even if the methods of securing results were not always the best, and that the Klan, as a fraternal organization, would tend to foster brotherly love in the College.”

Haverford News article “Rhinies Decide Against College Klan Chapter”

- Hampton University (a Hampton student traveled to the 1924 conference) has at least two significant race-related events from the same time period. As Hampton’s Archives page says, the “Indian Affairs Period” of The Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute hosted 1,660 Native Americans from more than 65 tribes, from 1878-1923, one year before the conference at the Woolman School. Additionally, in 1925-1926, there was a large movement in Virginia against Hampton’s relatively casual policy of integration in its auditorium. Anglo-Saxon Clubs clamored for an end to all integrated faculties at Hampton Institute. The Black-operated Norfolk Journal and Guide replied that white people already occupied all the major positions in Richmond’s Black schools, as well as the state school for deaf and blind Black people, and the state mental hospital for Black people—therefore the only difference with Hampton was that in there, “Hampton Negroes are treated as human beings and at the other places they are treated as inferior human beings”. This conflict ultimately led to Massenberg Bill of 1926, which segregated all theaters, auditoriums, and places of public assembly across Virginia.

- An aerial view of Haverford’s campus from the same year as the

Aerial view of Haverford College in 1931 1931 conference, providing a visual on what the institution looked like at the time its students were attending the conference at Bryn Mawr.

- Bryn Mawr has held competitive fire drills.

- An article on a fire that started in the campus’s “old infirmary.” Two students were caught in it, one of which became “enveloped in a sheet of flame,” but it was successfully put out with a fire extinguisher. The writer commended “the stolid common sense of the Italian workmen to whom a fire extinguisher is a fire extinguisher and to be used alike on women or on wood.”

- A series of short articles on a 1915 alumni fencing tournament held on the roof of what is now the Campus Center. (I collected these with great enthusiasm because I am the current Club Historian of the Bryn Mawr Fencing Team.)

- Several articles from 1914 about the stories of Mawrters who were caught in the outbreak of World War I and had to make their way back to America.

This content wasn’t relevant enough to contribute to the exhibit, but it’s nevertheless interesting to know about; its existence as ‘other’ details highlights an important part of the research process.